- Home

- Rebekah Gregory

Taking My Life Back Page 6

Taking My Life Back Read online

Page 6

He let go. We moved on. I never looked back.

By that time, we girls had spent enough time with Mom and Tim not only to warm up to Tim’s presence but also to be acutely aware of the difference in how he treated her, as opposed to how we saw our father treat her. Nobody needed to lecture us about it.

How refreshing it was to come home and be happy to walk in the door without that cringing feeling that braces you for trouble. We now knew firsthand how it felt to have peace in the house.

Peace in the house. It’s comfort for the soul. Test everything else that goes on in your home against the idea of peace in the house. Anything that passes this test is good for you. We had waited a long time for this.

About a year after Mom and Tim got married, when he formally adopted all three of us, we started calling him Dad. He had never been married before Mom came along with us three girls. I honor the courage of any man who would do such a thing. Although I’m afraid we made him work for his welcome, not only did he do exactly that but the process also gave him plenty of time to get to know us and see what he was getting himself into. He embraced the whole thing.

After the visitation ended and our home life stabilized, this new peace in the house was like water in the desert, but it didn’t undo the counterfeit “lessons” my childhood mind took from everything leading up to the divorce. Any child who survives a dangerous home will go on and perhaps do well in life or even achieve great things. But every instance of unearned anger or unacceptable insult lands hard, like a heavy stone, and the memory of it remains.

The poisonous lessons I took from the broken marriage had to do with never again allowing myself to be responsible for a disappointed father—or for being a disappointment at all. I vowed to make sure everyone around me was happy and became a dedicated people pleaser, turning up the Sad Skill to maximum power.

No pressure.

We children of divorce, as adults, can easily look back and see how wrong we were during those years to assume there was anything we could have done to keep the family together. But at the time I had no tools for measuring any of those things. I had to let that part go.

The way out was to keep it light. Keep it all smiles around friends within our church congregation as well as friends from school. The Sad Skill helped me to avoid conflict but it also isolated me in a shell of well-intended falsehood.

I’ve met many people, Christian and nonChristian, who’ve described the dangers of getting lost in the attempt to please others to one’s own detriment. Like them, I successfully managed to avoid setting off family outbursts at home but I failed to realize that there weren’t going to be outbursts like that in our new home. And in our old home I hadn’t been the one causing them, not even when I was the focal point of the reverend’s rage.

When you’re dysfunctional you remain blind to simple logic and ignore evidence that is right in front of your face. And so I never felt safe in letting my guard down. This was not a reaction to our new household with Tim; it was a measure of how sticky those explosive episodes from our prior household remained for me.

I made weak attempts to discuss this with my mom but at age fourteen I couldn’t articulate the problem. With a level of naïvety that I hope I’ve now left behind with my girlhood, I entered a period of spiritual hollowness without even realizing it.

My father’s itinerant preaching moved him from one church to another, and he alternated his pulpit work with the night shift at a local casino. I’m sure he could explain that combination, but for me it added to my already suspicious view of his version of religion.

On the one hand, there were rare occasions when I could feel the hint of God’s presence in my life, just enough to keep my heart open to him. But on the other hand, the religious demands, rules, and expectations, as I heard them from my father, felt more like things a lawyer would say in a court of law—harsh and full of condemnation, delivered with angry rants. I could feel my heart burning up. I felt my life with my father to be nothing like a life following Christ and that it contained nothing at all that brought to mind a loving God. But I was still too young to separate the message from the messenger.

I avoided turning to Scripture for guidance because I had heard Scripture used so often to justify outbursts. The rage and violence of those outbursts were presented as righteous anger and legitimate punishment, but they were at a level far beyond anything that today, as a parent myself, I could ever call legitimate.

I could clearly remember childhood moments of feeling close to the Lord and also feeling certain I would never lose touch with his presence. Especially when I was up in that backyard tree. But those lovely moments had become memories of things I no longer repeated.

I was in the proverbial closet—the Obedient Preacher’s Daughter, pretending to be a Christian while I went through church rituals that felt unnatural. I couldn’t have told you what I did or didn’t believe about God with any certainty.

In the days since the Boston Marathon bombing, it’s been remarkable to have met so many people whose past experiences match mine, in terms of how their spiritual wakefulness was boosted not just by their relationship with the Lord but also by their relationship to their place of worship. But for some the opposite was true, and they were damaged by the personalities they found there. That was also the case for me.

At the time there was no way for me to tell if I could ever find a personal, deep relationship with God. I suppose the hollow smile of a “church lady” begins with the hollow smile of an Obedient Preacher’s Daughter.

−6−

All Hat, No Cattle

I spent my teen years as a chameleon, seeking out a variety of crowds and becoming whatever was needed in order to fit in. Most of the time I was too good for my own good. If I couldn’t be bouncy and cheerful, I could at least keep quiet about any turmoil of my own. And I did so as if I were on a mission, though I had no idea what that mission was supposed to be.

Even if the exterior of your story is vastly different from mine, you may resonate with the challenge of being spiritually alive and socially acceptable at the same time. I was that way too, but while the desire to fit in is a common concern, I took it to the nth degree.

It felt normal to do that, which means it looked pleasant to others. The Sad Skill schooled me on how easy it is to become your own worst enemy beneath a layer of falsehood, no matter how well intended it may be.

If I had been more honest with myself then, I might have done something to open up and relieve the unnecessary pressure of a hidden existence. But I spent the next four years letting the motions of going to church and singing hymns and praying out loud substitute for a living spiritual life. Combining that with my self-appointed role as a people pleaser on steroids, I trapped my emotions behind locked doors, and they reacted by building up to the point that I became a human pressure cooker. Ironic, I know, but true.

Since I was still a relatively timid sixteen years of age, I certainly wasn’t the type to explode and take it out on others, but all that energy had to go somewhere. So it blew through my immune system instead and shorted out my physical health.

A sudden onset of dizziness and fainting spells hit me and refused to go away. These fainting spells became frequent and dangerous. It got to the point that if I had been sitting or lying down for any period of time, a wave of dizziness would hit me when I stood up. It was sometimes so strong I had to sit back down and get up again very slowly. Sometimes I became lightheaded for no discernible reason and would stumble or fall down. Naturally, this was hard on anyone I was with, only in a different way; they were left with the task of explaining to themselves what they were seeing.

Jokes about being tipsy got old fast.

I was too blind to the cause and effect to deal with the core problem. However, the medical explanation emerged when my doctor diagnosed Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (it helps if you read it out loud). Thankfully, it’s also abbreviated with the acronym POTS. This neurological illness

involves the brain sending out the wrong signals when it comes to adjusting heart rate and blood pressure. It has a severe impact on normal movement. The illness is more serious with adults, since it can stay with them for life. Fortunately for me, it only has an average course of two to five years when it strikes teenagers and young adults. After that, this illness, which is not well understood, runs out of steam for reasons that are also not well understood but that are fine with me.

POTS tends to strike people who have suffered physical trauma or teenagers whose bodies undergo great stressors. Sound familiar? The warning lights were blinking away, bells were ringing, and buzzers were going off.

If I had been in a more spiritually awake condition, I believe my resilience could have been strengthened by my struggles. Instead, the conflict I carried around inflicted such damage on my physical system that it left me with potentially deadly fainting spells.

As you would expect, my ill health affected everything I did. On bad days it was a problem to leave the house at all. It seems clear to me today that this illness spanned the border between mind and body. I look back on it as a manifestation of my self-styled emotional prison. These short circuits in the brain’s signals were the result of living inside a pressure cooker of my own making, boiling over heat I put there myself. There seemed to be no end to the cost of living as an Obedient Preacher’s Daughter.

For the next four years, the illness remained stronger than I was, until I reached the age of twenty. That’s when it slowly tapered off. I had no sense of control over any of it. To me the whole thing felt as if it had showed up without warning, operated on its own schedule, and departed when it was done.

For this, my faltering faith just couldn’t rise to the occasion. Even though I became aware, for the first time, of what you could call “the bigness beneath every small thing,” and I believe Jesus was reaching out to me, his whispers were lost on me. I was clenched too tightly to respond. Regular trips to the hospital were a part of my life. It felt as if my father’s words, the ones stuck in my memory, were prophecy: I was weak and I really would turn out to be good for nothing.

My downhill slide was powered by my own confusion. On the surface I was not a rebellious kid and I appeared to be in sync with my peers. I mostly did whatever I was told by someone in authority.

But that was all exterior work. My inner life, prayer life, and determination to live in Christ were starving. A Texan phrase applies: I was all hat and no cattle.

Under the persistent drip of POTS symptoms, I could never tell when my neural wiring would betray me. The social isolation I had already experienced was amplified now, and each new blood pressure episode landed on the fertile soil of that old voice echoing up from my memory, assuring me that my body certainly couldn’t be trusted, since I myself could not be trusted to do anything right.

I became extremely shy in public but remained outgoing at home, almost like two different people. Back then I had no idea how many shy people are like that. I was already a reader, so I became a reader big-time. I could lose myself in books and further developed a love for expressive writing and storytelling.

But as far as my self-worth was concerned, the takeaway was that I was worthless and bound to remain that way. I wasn’t conscious of having that viewpoint; it just felt true. I befriended everybody but myself.

For those years, the Obedient Preacher’s Daughter was my fallback position. When I was able to go to school and attend outside functions, I could make myself seem to fit in, but I seldom let anyone get close. My father was long gone, but the messages from my childhood held me firmly in their grasp.

−7−

Dangle Time

In the weeks after the Boston Marathon bombing, I could feel the same temptation to despair that was such a problem during my teens. The feeling had a heavy downward pull to it, like swimming with a weight belt.

The difference, this time, came in moments of clarity that I didn’t have back then. Those moments, brief as they were, were like dappled bursts of light amid the grim tapestry of the hospital routines. They bolstered my heart in the midst of the constant physical assaults from the drumbeat of surgeries every second or third day.

Such moments allowed me to perceive the unique ways that my injuries set me apart from my prior self. Each of them was a reminder of what the Sidewalk Prophets were talking about when they sang “if I need to be still give me peace for the moment.” As everyone who suffers traumatic injury knows, our limitations will confront us throughout our recoveries, all day, every day, and it was no different for me.

I developed an ongoing process, matching up the differences between that old normal and this new one in the back of my mind. This all went toward learning how to be this new version of myself.

It was an urgent effort. As soon as I settled in at the Houston hospital and got my head clearer for the transition back home, it was time for a more invasive surgery than any of the operations I had gone through in Boston. We were still fighting to save my left leg, so my surgeon removed a large flap of my back muscle and surrounding tissue to fill the hole in my left foot, where the chunks of bones and surrounding muscle had been blown away. The intention was to give new flesh something to build on.

They also peeled another large rectangle of skin from my outer thigh to cover the foot graft. This thigh wound had to be kept moist for many days after the operation, regularly cleaned, and then re-covered by artificial new skin to keep the infection that was already there from the remaining shrapnel at bay.

The graft on my left foot required the entire leg to be elevated at all times at a level above my heart. In the first two weeks, I couldn’t lower it even for a moment or else the shift in blood pressure to the newly forming vessels would likely burst them. No doubt we can all visualize the technical challenges involved in constantly keeping one leg elevated above your heart for twenty-four hours a day without needing to hear further details.

Once that critical two-week period passed without problems, the doctors deemed me ready to go home. I still had to keep my leg elevated, but now I could have five minutes a day of what they referred to as Dangle Time.

Five minutes of Dangle Time might not sound like a big deal. Oh, but it was. It still is, every time I think of it. Consider the joy of a young dog released into a big, sunny yard after a night spent in a cold basement. That’s Dangle Time.

Within those brief few minutes, I could hang my legs over the side of the bed and even use the bathroom. True, I still couldn’t take a shower instead of using the tub, and I couldn’t piddle around in there (five minutes passes quickly). But Dangle Time was a chance to come up for air and remind myself that the whole idea was to get back to independent movement.

Mmm, Dangle Time. It would almost (operative word, almost) be worth it to go through elevating your leg over your heart for two weeks just to feel the exquisite relief of simply being able to lower it back to a normal position. Let’s return for a moment to that excited young canine bounding out of the basement and into a sunny yard. A world of possibilities.

We learn to be grateful for crumbs. And the experience of gleeful freedom is hardly limited to dogs, since those few minutes a day no doubt feel the same way to a locked-down convict. Five minutes in the exercise yard, kiddo. Spend ’em wisely. Anytime is good time if it’s Dangle Time. And so even though Dangle Time for me only meant a few minutes in a vertical position, still: Hallelujah!

After those seventeen days in Houston’s Memorial Hermann Hospital, it was time to try going home. The doctors and staff there had been kind and professional during my stay, and I alternated every few minutes between being eager to be gone and afraid to make the jump. I yearned to resume a home life with Noah, but I still felt so weak. There were weeks and months of in-home nursing care and recuperation ahead.

Every new day seemed to be a bigger battle than the day before. I was mentally and physically exhausted. But once the schedule was in place, I committed to going through with it. On June

10, fifty-six days after the Boston Marathon attacks, they wheeled me down to my mom’s van and propped my leg on pillows for the ride home, ready or not.

Somebody slid the van door closed, and we were on our way. For the time being, Noah and I were going to be at my parents’ house, because I needed so much bedside care. I had already been on IV antibiotics in the hospital and had to continue with the IV for six more weeks at home. A health nurse had to come every day to change the dressings on my wounds.

My left foot looked like something that belonged on an alien creature, a misshapen appendage with purple-yellow coloring. The graft had to be checked throughout the day to watch for possible tissue rejection. To keep it from failing, a Heparin shot was to be administered into my stomach every night to prevent blood clots.

It’s more accurate to say it would be injected at night into what was left of my stomach. At my final hospital weigh-in, I tipped the scales at seventy-nine pounds. This is just a bit more than half of my healthy body weight. The long slog of surgeries, anesthesia, and appetite-killing opioids had turned me into a convincing portrait of a patient sent home to die.

My fantasy of going home and returning to a life that I still recognized was pretty badly shaken by the reality of the experience. Somehow, in preparing to transition out of the hospital and into home recovery, I visualized myself as being closer to normal health, as if returning to my home environment would somehow restore the old normal that it represented.

Not that I thought I’d be cartwheeling around the front yard, but my images of home life in recent years were happy ones, and I was strong in all of those scenes. The abrupt surprise was in returning to those places only to get another jolt from the new normal.

Unlike the healthy and independent woman I had been, in this new normal I still had the same ongoing needs that had been addressed in the hospital. Only now they had to be taken care of at home, by family members. Our backup was to dial 911 if the wounds became septic, and that was it.

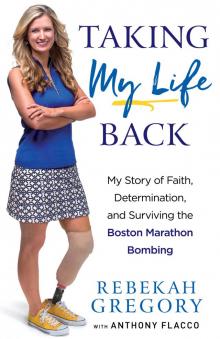

Taking My Life Back

Taking My Life Back