- Home

- Rebekah Gregory

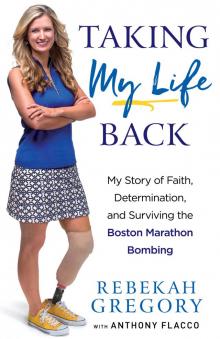

Taking My Life Back Page 7

Taking My Life Back Read online

Page 7

My brief experience at the Spaulding Center had taught me how quickly our bodies can fall to infection, so I had a healthy respect for watching over the surgical and shrapnel wounds. This meant that the road ahead would require a lot of energy from the rest of my family.

That didn’t change the fact that after years of being on my own, it was hard on my ego to intrude on my parents’ home this way. My youngest sister, Allie, was only eleven at the time, and the sudden change in her home life was far from ideal. It had to be hard on her, but she pitched in and helped me with the challenge of washing my hair with my leg elevated, among other things.

How blessed I was to have this support system and such loving people around me. Consider any victim of a massive injury who must return home to live alone or recover in the hands of strangers. No doubt their degree of difficulty is amplified many times over. I would have had to remain institutionalized or have constant in-home care for many weeks to come if not for all these people and their loving concern.

I’ve saved the best for last in this chapter because it really is the secret of how I was able to face this phase of the recovery with a brave heart. I say that even though I was fighting off a full-blown panic attack by the time Mom’s van pulled up to the house and it was time to wheel me in.

In that panicked state, I was suddenly overwhelmed by the tasks ahead. The ride home from the hospital made me fearful of yet another inexplicable attack from a random source of evil. By the time we pulled up to the house I had convinced myself there was dire danger in every direction. It was that same sudden sense of doom that anyone who has experienced a panic attack would recognize. Real or imaginary, the sense of danger tightened around my neck like a noose and left me gasping for air.

When the van door opened and Mom and Dad prepared to lift me out, Noah came running up, full of infectious delight to have his mom home again. And it was then, with one sentence, that my little boy turned my panic into determination.

“Don’t worry, Mom,” Noah whispered into my ear while he leaned over to hug me. “We’re never leaving this house again.”

He said it to console me, of course, to let me know the worst was over. But he unintentionally made his own trauma clear and, in that instant, slapped my panic attack right back out of me.

I couldn’t allow myself to be fearful or to withdraw from the world because my son had to be able to go out and engage with that world. There was no way I could allow him to think he should hide from life, even though he had encountered terrorism and its evil work so early in his own. His recovery was tied to mine.

And so, just as he had done for me at the finish line of the marathon, when my concern for him kept me rooted to the spot and determined to see to his survival, he focused my aim once again, simply by virtue of his presence in my life and his love for me, reminding me that being his mom was the central blessing of my time in this world.

The dreaded new normal became a bit less frightening after that. The old normal was gone, but I was home.

−8−

Pushing the River

I was twenty when Noah was born. When I became pregnant at the age of nineteen, my relationship with Christ was strictly formal, all too hollow at the core. I was absent without leave, and the consequences spun my life’s path off at a sharp angle.

I was still in college and working to help pay bills, and I wasn’t centered enough to realize that my way of making myself “safe” was unhealthy, with all this weird social conformity I felt compelled to use. All sorts of sharp costs began to hit me as a result of surrendering my own will to others.

After graduating high school, I had gone to Eastern Kentucky University intending to study nursing. But after a year of that, my sister Lydia became ill with heart trouble. I moved back home to Lagrange, Kentucky, to get a job and be closer to my family.

I wandered onto the wrong pathways.

I started hanging out again with a guy I’d known in high school when we both worked part-time jobs in the same town. At that time, we had been only friends. Now that I was back home from college, we were both at a New Year's Eve party I hosted at my new apartment—the birthday of a mutual friend of ours happened to fall on the same day, and there was a lot of drinking.

He stayed that night when I should have sent him home. This behavior was so uncharacteristic for me that by morning I felt steeped in guilt and was filled with a sense of lingering dread. Talk about an emotional hangover. I was about to get smacked with the brutal reality of how fast things can happen if we lower our spiritual guard, even for a short time.

Two weeks later, a home test confirmed that I was pregnant. The impact of this news was like the floor giving way and dropping me into a pit. I have to confess that under these circumstances, the miracle of birth and the joy of parenting were not my first thoughts. The crush of responsibility was like a ton of rock, with my self-respect buried somewhere beneath it.

Since we can’t make up for a mistake by making another, I was faced with the realization that there was no way to keep this from my parents. And no way to sugarcoat the news. It could hardly be concealed for any length of time. If I waited that long, it would surely be seen as a betrayal.

So I had to go and admit my foolishness to two people I greatly admired, whose good opinion of me was most essential at that time in my life. In order to simply wake up and start moving around in the day and feel okay about myself, I needed their good esteem.

My true spiritual bottom-out occurred days later, on the drive over to my parents’ house to let them know. They were, and are, devout people. I knew their Christianity was sincere and that they lived their lives with a strong sense of the importance of honorable behavior. And now I had to bring them this news of my personal lapse in judgment and of the unplanned results. My heart felt like it sat about six inches too low.

I’m grateful to say that for all of their disappointment and pain—which were abundant—their love didn’t fail me. There was never any talk of aborting my child. Any regrets they might have had about the manner of conception were tempered by the knowledge that a new member of the family was now on the way. The rest of our concerns had to be about bringing a healthy child into the world.

Their kindness prompted me to do everything I could to own all of the consequences of my choices and to protect this new child. I would work as many hours as possible to prepare for taking care of this baby and find ways to continue my education once my child was born to maximize our chances of having what we needed.

I welcomed the child in spite of my concerns over my failure of judgment. I knew what it was to have a deeply loving and dedicated mother, and I was filled with the desire to let that boy or girl know what it was like to be brought up in the world by a loving mother who could be trusted. I wanted to honor the gift of life by bringing a healthy baby to term and then nurturing him or her with all of my love and energy.

So while I realized that my sense of guilt brought nothing to the table, my loss of self-confidence was a real obstacle when it came to visualizing answers and solutions. I didn’t lose my faith in the Lord, but faith in my own judgment collapsed.

In that state of mind, I began the pregnancy determined to fix everything with a relentlessly positive attitude. My sense of shame overcame my faith in redemption, and I covered it all with smiles. I also went from being determined to being obsessive, at work and at home, as if a single mistake would break it all. I wouldn’t allow myself to put real trust in God’s plan for me. I remained a closed loop while I pushed myself to work harder.

As a result, before long my physical resistance was shot. Apparently, I have one of those bodies that works as a spiritual circuit breaker. Five months into the pregnancy I went into preterm labor and was admitted into the hospital, where I was told that I would stay until it was safe to have the baby.

The doctor’s plan worked, and after uncomfortable bed rest and around-the-clock monitoring, three months later a healthy baby boy was born. Suddenly, my ne

w son, my little boy Noah, was there with us all. It was time for Mommy to deal with life as a duo.

I know I was experiencing a deepened relationship with God just because of Noah and the miracle he turned out to be. I was thankful beyond words for the blessing of this child, but I thought this meant I owed some kind of spiritual loan, meaning that I didn’t deserve the grace that was there for me.

I forgot that grace isn’t something you earn. It is given freely.

Naturally, I never thought of it that way then. Why is that so hard to see in the moment? Because I missed it. I just squinted harder and leaned into the wind.

−9−

The Mom Machine

I became a mom machine after Noah was born, focusing on getting every moment right. I had wonderful parents who were willing and able to help me care for him, which meant I could go to work and know he was safe.

I had taken a job at a dialysis clinic, where they trained me to be a dialysis technician. It was a short drive to the clinic but a large cultural leap. That part of town had taken a drastic downturn and was now a seamy neighborhood that seemed to ooze hard-luck stories. I worked twelve- to fifteen-hour shifts, three days a week, and reported for work at four in the morning. It took us two hours to prepare the chemical mixtures used in the filters, see to it that all the machines got set up, and get the clinic ready to receive patients when the doors opened at six. I was often there until six or seven in the evening.

A few of the patients were children or adults with inherited kidney problems, but many of the patients had physical systems weakened by alcohol or drugs, and the fact that they had life stories to match was often plain on their faces. Although I was hardly a sheltered child, some of those individuals showed levels of misery and desperation so extreme that they cried out to me.

It was a constant study in human nature to witness the way that enduring difficulties will cause some people to shrivel into bitterness while others will find their strength and rise to the occasion. I didn’t know it then, but I was in the middle of a lesson in empathy. Many of the patients became quite familiar to me, and I felt attached to them. Their welfare, as far as this vital process was concerned, felt personally important to me beyond the call of the job.

You see where I’m going with this, right? How could I have known that I was being shown the stuff I would need to survive down the road? Does God help prepare us in advance for traumatic events, or was this truly a happy coincidence?

No matter where you come down on that, in the stories of these men and women who appeared to be so different from me, I received countless life lessons in attitude. The ones who thrived appeared to possess some essential form of resilience. They clearly had their struggles to contend with, but they were not downtrodden. Somehow, these individuals had come to a place within themselves where they could wear that heavy yoke of routine physical misery. It’s nothing anyone would ever learn to like, but the resilient ones seemed to regard the procedure as being akin to stopping in to have their car serviced so it can move on down the road. It’s not possible to lie to yourself about the situation when you have to show up and ride the filter system on a regular basis. All you have is attitude, the way you insist on relating to the cards in your hand.

I saw the truth of it: how tiny course corrections to one’s attitude, administered throughout the day, have enough collective power to completely change your experience.

Patients came in three times a week for at least three hours, maybe four. Some then went off to work while others were too sick to hold a job and had to battle boredom and the creeping sense of uselessness that haunts any long-term patient.

Treating people in such difficult circumstances, I tried to combine smooth, deft treatment with a positive and attentive attitude. I’m sure they all appreciated that, but some were either too ill or too depressed to engage with me about much of anything beyond the required discussion of the process.

Others, however, could and would relate to me in a revealing manner. I was especially glad for the emotional experience provided by this difficult job when I did my own time in the hospitals of Boston and Houston and in recovery at home. I believe that the more you know about the ways others handle their difficulties, the better prepared you can be to carry your own.

Although the dialysis job helped cover the bills, the brutal hours made me think twice about it as a long-term job, so I transferred my college credits to a community college to finish my required classes. This would put me in a position to get into nursing school later, and dialysis work could be a fallback position if I needed work while looking for a job after graduation.

Given those hours and with a little boy at home, I had almost no time for a social life, but that didn’t stop me from trying to have one. I dated a lot, but since I never wanted to get close to anyone, it was always very hollow. I didn’t mind the dating part but settling down was something I didn’t want any part of. Fortunately, I had been friends with Karah, my cousin by marriage, even before Tim and Mom were wed, and she also worked at the dialysis center. So she knew firsthand how difficult our work/life balance truly was.

We tried to still socialize on weekends outside of work, and if we couldn’t, we talked on the phone. We would be exhausted but still managed to stay up chatting into the night until our alarms were ready to go off for work at three in the morning. My life had no balance. There were not enough hours in the day to do everything I wanted. Karah was one of the only people who truly understood that.

Noah made it all worthwhile, though. He was a bundle of energy who seemed to delight in living. At this point in his life, Mom and Dad were such a strong addition of love and support that I believe he felt secure in his home.

Having a child imposed a level of maturity on me that I was glad to embrace. Simply holding him and drinking in his presence, knowing that his life and future were in my hands, convicted me that I had to do right by him.

Since I had the wonderful luxury of Noah’s loving grandparents to back me up with babysitting, I pushed myself to work hard while he was too small to miss me in hopes I could secure a better job with better hours before he got older. I wanted to do more than cover the bills. I wanted to prepare to take a major step up in our lives within the next few years. Whenever I heard the phrase “God helps those who help themselves,” it always sounded true. I followed it like a beacon, and it worked well—for a while.

As you may have already screamed at the page, I forgot all about the wisdom of moderation.

Then early one morning I was driving on a narrow and unlit stretch of interstate between my house and the dialysis clinic when a deer jumped out in front of my car. I realize it’s pretty unlikely that the creature did a deliberate swan dive out of the bushes and into my path, but it sure looked that way at the time.

Perhaps if I had been less fatigued, my reactions would have been faster. As it was, I responded with groggy reflexes that were not up to the challenge. Before I could hit the brakes or swerve, there was a terrible crash and an impact that felt like hitting a wall.

The deer was killed right away. Its body flew up over the hood and into the windshield, where it bashed through the glass antlers first. I instinctively threw up my arms at the moment of impact, and they were in that position when one of the antlers pierced my wrist.

The car flipped over and ran into a deep ditch, and I was knocked unconscious when my head struck the driver’s side door. The backseat was totally gone.

It was just as well that I wasn’t conscious, because rescue was unlikely and the panic would have been bad. It was around four in the morning on a lightly used section of highway, and in order for anyone to help, they had to see my car down in that dark ditch. Rescue wasn’t likely to come from anyone driving a car.

But soon a large truck came along, and the driver’s seat was high enough off the ground that he could see down into the ditch. He spotted my car and called for help.

When I came around, I was trapped in my seat by the w

reckage, staring a dead deer in the face and feeling the pressure and pain of my right wrist.

It seemed like forever before help came, although it was probably only around fifteen or twenty minutes before EMTs arrived with an ambulance. They covered me with a tarp for protection and cut me free. Once that was done, they put a neck brace on me, lifted me onto a gurney, and transported me to the University of Louisville Hospital. I received treatment for the next several hours.

Six bones were broken in my back, and my neck was sprained. The wrist puncture was clean enough that they used surgical glue instead of stitches to hold it together. The doctors assured me that if I had not been wearing my seat belt, I would have died.

The follow-up was two weeks of bed rest. Since Noah was still a toddler then, you can imagine how well this all went over.

I make it a firm policy that when God pins me to the driver’s seat with deer antlers, I give him my full attention. There was no longer any doubt that I had to find some way to trust in the Lord that would allow me to ease up on the throttle. That simple lesson had just been beyond me, until then. Happily, this time my slow spiritual learning process actually kept up with the challenge.

I am so grateful Noah was at my mom’s house when I hit the deer. As I’ve said, I don’t claim to know how much God intervenes in everyday affairs. There is always the issue of free will. I know I consider it a true blessing that Noah was with my parents instead of with me when the crash took place.

My mother later pointed out that I set myself up for it, trying so hard that I was sure to crash somewhere, whether it was a literal crash or some other form of self-made disaster. My cousin Karah was less blunt about it but seemed to share the opinion. I had been clinging to my inner tension like someone who has grabbed a live wire and can’t make their muscles let go. Reality had to pin me down to stop me.

Taking My Life Back

Taking My Life Back