- Home

- Rebekah Gregory

Taking My Life Back Page 5

Taking My Life Back Read online

Page 5

It wasn’t even a question really. It was an affirmation. There was no doubt she meant it. Some form of divine inspiration had replaced this girl’s grim ordeal with a revelation of peace and joy that radiated from her. For me, it surpassed all understanding.

I was suffering in my own situation while she found beauty in hers. We only had time to exchange a few words before she left the elevator. I stood watching her go, my own problems forgotten.

Humility was my only possible response. It was a complete revelation to see that girl, so much more ill than I was, finding the beauty surrounding both of us that I had missed. This feeling was new to me. I’d been humiliated at home many times, but an attack on someone’s self-esteem doesn’t result in humility, only shame.

Those few moments with her made a deep impression on me. She left me wanting to discover the source of her gentle self-assurance. I had made a public profession of faith at age seven and had been baptized by my biological father. But I was far from understanding the Christian faith and from having a living relationship with Christ. My own conflict over what I heard in church and saw in daily life had left me alternating between faith and fear.

True prayer entered my life for the first time on that day. This was not prayer as an imitation of the behavior expected from an Obedient Preacher’s Daughter but rather prayer that was an act of reaching out from the deepest parts of myself to commune with a loving God.

Of course, my spiritual eyes were just beginning to open, and while I had been led through all the motions of baptism and biblical teachings, I was not yet saved in the sense of fully and consciously embracing Christ. That was yet to come.

Still, my journey began back there in that elevator. It was ignited by grace delivered by a beatific child whose load was heavier than my own. That frail little girl showed me the direction of the Lord’s footsteps. She didn’t have to speak a challenge for me to follow her; she embodied the challenge.

More than anything else, that’s what she awakened in me: a true sense of having a direction to follow, as opposed to simply knowing what I was expected to say and do.

I was still a long way from living my life in Christ and had to overcome my background of what I saw as religious falsehood and spiritual emptiness. But now I was hungry to know peace within.

It was not a booming revelation; it was more like the first thin ray of sunrise. The peaceful silence of my old perch up in the backyard tree was replaced by a drive to live somehow closer to the Holy Spirit. I had no idea how to proceed, since all the skills my background provided seemed phony and ineffective. My steps would be small and slow, but for the first time I could sense the direction I needed to travel.

When the bombs went off in Boston and while I was still fighting an uncertain battle in the hospital, my sense of responsibility for my son filled me with the will to rejoin life with him. Today I realize I got the model for this kind of determination from my mother. That goal seemed impossibly high for a while, and when I dared to think ahead and imagine how we might actually get along in the world, I couldn’t envision a way out. But what I missed at the time was that my prayers were already being answered. My drive to make that life with Noah happen helped to keep me strong.

This was again mirroring my mother’s way of living in Christ. She was never one to preach the gospel in my face or to wave a sense of righteous superiority around.

She never had to harp on the lesson that talk is cheap and that what you do is who you really are. She just lived it out every day and made it real. Faith may be invisible, but its effect on behavior is not. She taught by doing, and it’s hard to argue with what you see before your eyes. I didn’t have much to rebel against.

As a girl, I straddled the clear reality of my mother’s faith and spiritual dedication on the one side and the distorted notion of Christianity I had learned as an Obedient Preacher’s Daughter on the other. The result was that my conscious spiritual life nearly shut down altogether while the part of me that learned by example continued to absorb the message that there had to be something more, something greater than me.

Every eight-year-old girl wants to idolize her mom. My loyalty to Mom and to what I felt to be the truth caused me to admire her and want to be more like her. At the same time, my father’s whole world represented treachery to me. I’m certain he saw it differently, but that’s the effect it had on me. My sophistication was inadequate to tease apart those influences and pull the truth away from the falsehoods.

This battle within me wasn’t going to resolve itself overnight. And by the time Mom pulled us out of there, I had already developed a coping mechanism I call the Sad Skill. I gave it that name because a skill takes real effort to learn, and the more this skill is used the more harm it does to the user. It is a skill of avoidance, temporarily delivering peace—or at least the absence of conflict—but pushing honesty under the carpet.

A person with the Sad Skill has the ability to thoroughly stuff negative thoughts and emotions deep, way down deep, maintaining instead a relentlessly cheerful demeanor and an inoffensive conversational style. When we employ the Sad Skill, it comes to be our expected mode. People tend to like it because we are giving away our energy and taking little in return. The bars that trap us inside the Sad Skill are made of other people’s expectations, but they’re created by our own behavior.

I only realized years later that the Sad Skill is widely employed, found in every walk of life. Furthermore, in the days since the Boston Marathon bombing, I’ve learned from the testimony of others that the unseen prison of the Sad Skill only grows in strength over time. It did with me, and I resonate with the stories people shared with me.

As a young girl, I got through my days by shutting down my feelings and personal needs in favor of pleasing anyone else who happened to be around. For me, the concept of feeling good seemed vaguely obscene. I wasn’t good enough to feel good. Indelible memories of my father’s tirades rebounded in the form of a compulsive drive to look good, smile big, and make others happy.

This is the Sad Skill at its heart. It’s not about bravely soldiering on in the face of things that can’t be changed, as almost anyone has to do from time to time and as some people do throughout their lives. It’s about hiding your pain so well that you even conceal it from yourself, assuring that everyone stays as content as possible while nothing gets fixed.

My self-appointed role became the “guardian of tempers,” seeing to it that nobody ever had a reason to be upset about anything. Or if somebody did happen to become angry or even mildly irritated, my self-declared responsibility was to make them feel better as quickly as possible, whether I had done anything to cause the problem or not.

I’m sure you already recognize this as a self-destructive choice. I do now—I didn’t then. With all the logic of one who has wandered away from God, I responded to my hunger by refusing to eat, falling back into old negative patterns that were more deeply ingrained than I realized. This made faith hard in those days, and today I believe similar forms of emotional trauma make it hard for many others.

Too often, when I prayed, it was only to fulfill the obligation to speak certain words into the air. That way if anyone was watching, I’d make a convincing “good girl” show and there wouldn’t be any trouble.

−5−

The Visitation Blues

My father’s visitation rights involved us girls spending every other weekend with him. His congregations knew him as their pastor. Of course, we saw the extent of his flaws, which must be true for anyone who lives with a preacher. As the oldest child, I’m sure the impression was strongest with me.

Any spiritual progress I made in those years happened of its own accord, outside the church and religion. It was powered by the enduring hunger left over from those brief moments, such as the moment in the elevator, when I felt what I can only describe as the presence of God.

By then I was old enough to understand that Mom had no choice in the visitation arrangement. If she challenge

d it in court and things went badly because he could outspend her on lawyers, or if his attorney worked up some unexpected legal move, she could be forced to give us over to him. I found the idea unthinkable, and so I was happy enough with everything about the visitation arrangement except the visitation.

As a newly single mother, my mom became the unstoppable worker bee. Once she got a good job and put away some money, we moved from her parents’ home to our own place while she kept plugging along, working and parenting on her own. During the next few years, my old demon of helplessness hit hard again while I watched her endure conditions so much harsher than she deserved.

She honored the custody agreement and surrendered all three of us to him on those alternate weekends. I knew, from the way she was with us the rest of the time, that she would have gladly filled her resulting private time with our company if she could have. That same measurement was the reason I was so uncomfortable in my father’s new reality as an itinerant preacher, one who was sometimes attached to one church, sometimes operating freelance, and skilled enough at dealing cards to always have paying casino work when God failed to provide. He wasn’t there much, even when we were at his place.

I know there was a part of him that wanted to be a good dad, or at least I like to think there was such a part of him. On visitation weekends, he may have been having such a difficult time of it on the personal level that he just couldn’t manage the energy needed to take care of us. I do remember one happy occasion when he sat us down to learn blackjack. It seemed like a harmless game, something we could all do together. We were happy because he used cookies for chips.

I always saw him as having terrible financial problems, and there was often very little to eat in his kitchen. He also had to work on many occasions when we were with him, so I wound up taking care of my sisters. The sense of responsibility was heavy because there was little I could do for them and not much comfort for us in that place. There were times when my own anger and resentment felt poisonous to me. Of course, the Obedient Preacher’s Daughter walled off most of those feelings.

This went on for several years after the divorce, until one day Mom sat me down with my sisters and told us she had been dating a man for a while and that they really liked each other a lot. She said his name was Tim Gregory, and it was time for us to meet him.

Within the following year, they were married. Tim proved himself to be an honorable man who was up to the challenge: taking on marriage, his first, to a woman with three young girls. I was thirteen at the time, and during my fourteenth year, Tim officially adopted me and my sisters.

Sounds sweet, doesn’t it? Almost greeting card-ish? It actually was, once all the dust settled. It’s just that the dust filled the air for a long time. A good share of that was my fault. Because I was so out of touch with my feelings, in my commitment to my role as an OPD, I had no idea how much suspicion I held toward any male who might have some sort of authority over me. When a new man was added to that mix—one with access to my mother—I saw nothing but trouble.

The poor guy had his work cut out for him. And it’s not like Tim is a creampuff. He wasn’t about to try to beg his way into our hearts, and if he softened his tendency toward sarcastic humor when we were around, I sure couldn’t tell. A few times one of us would try to “refuse” to go someplace when Mom attempted to take us somewhere with her and Tim, but they weren’t having a lot of that nonsense.

What we experienced with Tim was the opposite of what I experienced with my father. My father had seemed as though he really didn’t want to spend time with us and that we weren’t worth the effort. Tim wasn’t going to beg us to love him, but contrary to all expectations, he wasn’t going to go away either.

As time went on and his relationship with my mom continued to bloom, more than anything else, all three of us girls couldn’t avoid noticing that Tim was always there for us. He always showed up for the family, and he seemed to think we were important enough for his valuable time. He also treated us all with loving respect. Even at that age, I had a pretty good idea that this was a wonderful thing. And so keeping up an angry wall against Tim started to feel like a lot of work. I began to wonder what my objections were supposed to be.

In terms of my desire for a healthy and permanent family, in some ways it pains me to admit that I would have gladly lived with Mom and Tim on a full-time basis from the beginning. It wasn’t that I had no affection for my father, but in my eyes he was dangerously unpredictable. His emotional explosions were so frightening that I was completely unable to appreciate the other ways in which he may have fulfilled his role as our father. It felt like trying to accept being kissed on the cheek when it might be followed by a blow, or walking on the floor of a house with unseen places where you would fall through if you stepped there, but you never knew where they were.

After the separation, it was wonderful to have peace in the house at last, to come home and open the door without anxiety. But there is heavy emotional weight behind the idea that your home is a broken place. For the next three years, the thought of coming from a broken home was fresh in my mind. It had to be, because it was kept fresh in the minds of my peers by the visitation blues.

My sisters and I arrived at school on visitation Fridays carrying little suitcases packed for the weekend. We could stash these in the administration office for the day, but on Friday afternoons, when all the kids and their parents were streaming by, we had to sit on our suitcases and wait for my father to pick us up. Sometimes he showed up and sometimes he didn’t.

I know everyone has their story, and I’m sure he could explain how it happened, but on our end of things we were just out there, curbside. If he didn’t show, we had to go back into the office and have someone call Mom, who would have to leave work to come and get us. We all know how much bosses love it when their employees have to suddenly leave work because of their kids.

Let’s see, now: Did any of the other kids notice my sisters and me out there with our suitcases? Ahem. It might have been more obvious if we had sat under a Hollywood-sized spotlight, but there was plenty of attention to go around. Somebody started the rumor that our father was a “jailbird” and that this was why we lived with him only on weekends.

Of course, the rumor stuck. Kids would catcall while we sat on our suitcases, “Where’s your jailbird father?” A few of them openly predicted that the reason he didn’t show must be that he was “in jail again, ha, ha!” Good times.

I don’t know if I consciously withdrew from my classmates or if they just moved away from me, but those suitcases brought a lot of alone time into our school experience for my sisters and me. Whether or not my sisters understood the terms the older kids used, I know they felt the sting of ridicule clearly enough.

Visitation meant a weekend with my father’s unpredictable moods and with what I considered to be his distinct personalities. On a good day, we got the happy preacher teaching us card games. More often than not, though, we got the angry and offended man I knew too well. As the oldest, I carried the most responsibilities, but I was apparently a constant disappointment. Leaving a toy out, forgetting to make a bed, or getting caught watching an unapproved TV show could invoke outbursts of rage. I could tell that these responses were much too ferocious for the incident, but there wasn’t much I could do to shield my younger sisters from his rants. As the oldest, a lot of it came my direction anyway.

The visitation blues played its last stanza while we were at our father’s house for one particular weekend. It was a small place in a bad neighborhood, and he was gone for the day. It was hot outside, a real scorcher, and the air-conditioning window unit wasn’t working. For a while, we tried to pass the time by playing outside, but not only was it sweltering we also didn’t feel comfortable outdoors without an adult in that neighborhood. At least there was shade inside. So we went in where we felt safer, but in spite of the wide-open windows there wasn’t enough breeze to keep the room comfortable at all.

My sisters and I got a

long well enough, but they had no idea why we had to sit around in heated misery instead of just being back at home with Mom. At least they always brought toys from home to keep themselves busy, so we all just sat around in the stifling heat marking time. It could have been worse; at that point our father was dating frequently and oftentimes brought his dates home. On this day we were glad to be there by ourselves without having to also deal with our father and some other woman.

The afternoon wore on. Time dragged. The temperature inside got so hot that the house felt like a cross between a steam room and a sauna. My sisters began to get really distressed, so I took them into the bathroom and put us all in the shower, under the cool water. That was my best idea, and although I was only eleven at the time, even today I don’t know what else we could have tried. It worked well enough for a while, but it was quickly obvious that we couldn’t spend the day in a shower. None of us were at all clear on why we were having to go through all this. My sisters felt trapped and stranded, and I didn’t know what to tell them.

Their distress finally made me break down and call my mom, which was a real blow to my pride. Even though I was terrified of the punishment I could receive from our father for doing that, I was serious about my responsibilities as the older sister. I knew there was no one else to take care of them at that house and the situation on that day left me with no other tools.

So I explained to my mom that we were stuck in the stifling house by ourselves and had been alone for hours, and I was out of ideas on how to keep my sisters calm. I told her we didn’t understand why we had to be present for “visitation” when our father wasn’t there to do any visiting.

She stopped what she was doing and called the police, who came to get us, and Mom met us down at the station. We were out of there before he came home. It was our last visit.

The next day she got a restraining order against him and then took him to court. My dad wound up signing over his rights to all three of us, and that, at last, was the end of the visitation blues.

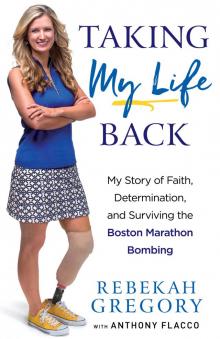

Taking My Life Back

Taking My Life Back