- Home

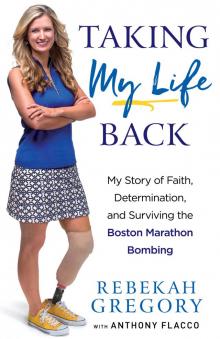

- Rebekah Gregory

Taking My Life Back Page 3

Taking My Life Back Read online

Page 3

I had worried about how to talk to Noah about what had happened to us, but since there was no way to sugarcoat it without some ridiculous fiction, I decided to just keep it simple. Give it a name. Give him a way to talk about it, if he wanted to, but not try to force anything out of him. Let the rest work out in its own time.

I knew he had to have picked up a story of some kind, although Dad said he hadn’t shown much curiosity about it. But I also knew he would look to me to describe this thing for him. The picture we made of it together would form his way of remembering it and of thinking about it far into the future. Like drawing a design in wet concrete, it was important to give him an image he could use before everything hardened.

We talked about how there had been two bad men who set off two bombs and hurt a lot of people they didn’t even know, but the police had caught them and now they couldn’t hurt anybody else anymore. Noah seemed fine with that description and didn’t express any curiosity to know more about the men or their motives. Bad men do bad things. He got it.

Noah and Dad stayed for a couple of hours, and in that time the procession of nurses and doctors kept on moving through the room and the daily treatments continued. When Noah overheard the staff members talking about how much weight I’d already lost, with repeated surgeries yet to come, he grabbed my untouched meal tray and insisted on spoon-feeding me the dish of Jell-O. My appetite was laid flat by the antibiotics, surgical anesthesia, and daily pain meds. I couldn’t do much more than swallow water.

Still, it turned out that Noah and I both needed the experience he was offering. He was gaining the assurance of helping his mom get better, and for me, I realized how much better the food tasted from his spoon. I ate the entire bowl. I tell you, lying there in that hospital bed, with him there next to me, serving me, was as holy and wonderful an experience as anything I have ever known.

The doctors had placed my damaged left hand in a large splint, which helpfully concealed the injury. Noah was adamant about signing his name on it. He was so proud to have recently learned how to form those four letters, and he carefully wrote them down with a serious sense of purpose.

It was the best gift I could have ever received. A sample of Noah’s first handwriting was going to be right there in front of my eyes for as long as the splint remained.

And from that moment, it was as if the letters he carefully printed contained so much of his innocent love in them that they radiated power. They didn’t stop the physical pain, but suddenly I felt more strength to endure it. My gratitude for the gift of his little signature overflowed.

I chose the name Noah for my son because I love the biblical reference in the Old Testament to the humility of Noah and to his great accomplishment. I consider it one of many blessings that my little boy has either rescued me from my own floods or given me reason to swim harder, time and time again. Then and now, my Noah keeps me inspired.

His visit that day went by too quickly, but I felt my energy draining away. When Dad saw that the time was right, he took Noah back to the hotel. Soon they would fly back home to Houston while my recovery continued in Boston.

Part of my joy of the day was seeing Noah lifted up by his visit. His beaming smile and happy energy were a relief for both of us. He had been stuck for five days in a room full of strangers, watched over by his loving grandaddy but still without his mom’s presence, enduring painful medical procedures. I don’t remember being five years old, but my memories begin a year or two later, and I clearly recall how long a week was back then. No wonder he was so visibly relieved.

My heart felt like a helium balloon that had just drifted up to the ceiling.

My mom was my connection to the outside world. One of the most important things she did for me was control what was kept out of my room, such as news of further miseries we could do nothing about. Her goal was to maintain a positive healing environment as far as the situation would allow. Now I can look back on it and see how wise that was.

During the hospital stay I continued to drop weight fast. Since I was already pretty slim when the attacks occurred, it was more than I could safely lose. It turns out that repeated surgeries are a very effective weight loss program. I was locked into a series of operations that had to be scheduled nearly every other day, with a day or so between each for recovery and to get most of the anesthesia out of my system before starting again.

I couldn’t eat after midnight on any day when I was scheduled for surgery the next day, and coming out of anesthesia I had no appetite. The next day I was free to eat if I could—but only until midnight, since there would be another surgery after that recovery day. During the recovery day, either the pain made food unappealing or the pain-relieving drugs again blocked my appetite. Move over, Weight Watchers.

With Noah back in Houston so he could return to school and so Dad could return to work, I was humbled by Dad’s quiet resolve and loving support. I was so grateful to know that Noah was safe with him, giving me the time and space to recover. My son had come so close to being taken out by that explosion, underlining his preciousness to me, which was reemphasized when the doctors told me I had taken so much internal damage from the tiny shrapnel bits that I was unlikely to be able to conceive a child again or to carry one to term. Another kiss on the cheek from the terrorists.

This was the life I had awakened to discover after the bombing, and my days consisted of being gradually pieced back together, day after day after day. The doctors were still trying to save my left leg, damaged far worse than my right, but a lot of the surgeries concentrated on a term I had never heard before: debridement. And no, debridement is not the process a man goes through to divorce his wife; it involves removing foreign objects from living tissue to minimize infection and inflammation. Debridement. Debriding. Debride. I could have gone a lifetime without learning those words.

They couldn’t debride the shrapnel bits out of me all at once. There were far too many. In some places, my flesh was so impregnated with debris that an X-ray looked like sprinkles suspended in Jell-O. Bits of metal and plastic were all through my thighs, back, and calves. The surgeons concentrated on getting the big pieces, but there were so many small ones that in order to remove them all they would have had to carve me up until my flesh was shredded.

For that reason, the debriding process went on for weeks. During those first few weeks, I was wheeled into surgery eleven times, with multiple surgeries performed under each session of anesthesia, followed by a rest day, for a total of dozens of operations. From the beginning, those days were a constant routine of cleaning the open wounds and changing dressings, removing stitches and putting in more.

The pain never got better, although I was clearheaded enough to realize that its levels were far less than I would have felt without the meds. I couldn’t move either leg at first. On the left leg, half of the fibula and many of the bones in the foot were all gone, just blown away, requiring the steel fixator. My right side had been ripped open by shrapnel and had stitches everywhere.

Any movement caused the pain to flare. I tried to find a position that might allow me any comfort at all, and Mom was endlessly patient in adding and subtracting the pillows under my legs. When we found a position that worked, it brought a few minutes of relief, but the pain always found me and crept back in.

A particularly kind resident observed that I had hundreds of stitches that had to be removed and restitched every time a surgery affected the areas, and she took over that challenge. So after she did her required rounds one day, she came in on her own time and carefully removed each stitch, one by one, and gently cleaned the wounds. There was no way to eliminate the pain of it, but her smooth and careful hands worked with such accuracy that she barely disturbed the flesh around each stitch as she cut it and pulled it out.

It took over an hour for her to carefully remove each one. It allowed me the least painful process that could be had, and at the same time it showed me her heart. What a lovely sense of mission she carried to work every d

ay. I was blessed by her outstanding show of skill and compassion.

My wonderful day nurse was Tracy, who was nearly six feet tall with short blonde hair and a lovely British accent. She was sweet and feisty at the same time, a blend of British and Bostonian stoicism. She was unfailingly attentive, even helping boost my morale by bringing in actual shampoo to replace the hospital stuff and washing my hair every two days. She said my hair was my crowning glory and I shouldn’t have to neglect it.

In the midst of administering frequent blood transfusions and IV meds and monitoring Mom’s assistance with wound cleaning, she treated me like a person—like Rebekah and not just another of her many patients. I don’t know if such things can be taught in nursing school. It seemed that Tracy just had this in her nature.

At night the level of care I received was no different. My nurse Naomi, who grew up in Falmouth and is about as Boston as they come, entertained me with her own life stories. She consoled me when my emotions became too much to handle on my own. Whenever she got a few minutes of free time, she would come back to my room to check in on me and oftentimes just sat and watched HGTV to keep me company. She did whatever she could to make me comfortable.

After thirty-two days, the staff decided I could transfer to a rehabilitation center and begin getting ready to go back home. My surgeons told me, “For now you can keep the left leg and try physical therapy; see how it goes.” This was a good piece of news. Everyone at the hospital had been so wonderful to me over the past month, but I was hungry to begin putting my life back together.

They transferred me via ambulance to Spalding Rehabilitation Center, where the doctors checked me in and said I looked good, ready to begin transitioning back home after a few more weeks. However, Murphy’s Law being what it is, later that day I noticed my left foot turning purple and beginning to swell. Of course, it had looked terrible ever since the blast, but this seemed different. It struck me as dangerous. I called a nurse and pointed it out to her, but at first she didn’t notice anything abnormal.

Hours went by, and my foot continued to swell and turn darker in color. I began to really get concerned. The foot pain was growing fierce, even compared to the pain of surgical recovery. And several hours later, when the doctor made his rounds, he took one look and immediately said the foot was infected and they had to send me back to the hospital for treatment.

I made no objection. In spite of all the pain and discomfort of my hospital stay, I had come to trust and rely on the staff in that place. Here, in this new environment, my intuition told me that the more vulnerable my condition was, the more I needed to get back under my hospital’s care and not worry about the rehab yet.

Within hours they had me back at the hospital, where immediate exams revealed osteomyelitis, a bone infection, in my more damaged left leg. The next day my doctors grimly informed me that the leg would have to come off. There was no time to watch and wait. The bone infection could quickly spread and prove lethal. They would do an exploratory operation the following day to determine the best place to do the amputation, then perform the main surgery. In the meantime, they kept me loaded with antibiotics to keep the infection from spiraling out of control.

By this point, after so many weeks, I wasn’t that surprised to hear this news. My right leg appeared to be recovering and seemed as if it could eventually regain strength. But my left leg had taken much more of the blast, especially the lower leg, simply due to the angle of the explosion. Even after weeks of recovery, it remained barely recognizable to me.

My story takes a sharp turn at this point, something that I can only describe as another miracle. My mother reached out via email, social media, and phone calls to everyone we knew and asked them to pass on her urgent plea for prayer warriors everywhere to pray for me. She heard back from people all over. In answer to her appeal, dozens of people prayed for me that night and the following day. Together they asked God to fill my body with enough strength to battle this new assault on my system.

This was not the first time in life that Mom had asked for prayer for our family—more specifically, for me. And it seemed that each time she did, we were able to comprehend just a little more of how powerful God really is.

The idea of amputation seemed to be for the best, and I hoped that was true, but by that point I had no idea. Events had taken on a heavy, inevitable feel. There wasn’t any debate involved over the surgery, or even time to think about it. Before I knew it they were wheeling me down to the surgical bay and putting me under again.

Time jumped, the way it always does with anesthesia—the lights go dark and everything flashes ahead—and the next thing I knew my awareness was returning and I was in recovery.

Pretty soon my doctor came in and explained that when they opened my foot and leg, they discovered that my body had been able to clear the osteomyelitis without the operation. In that very short window of time, an infection that was so bad it threatened my life and made amputation appear necessary had simply . . . gone away.

So they stitched the incision and decided to leave everything in place. “We still want you to keep your leg,” he told me, which sounded good, except that this would now involve more hospital time while we watched to be sure the infection didn’t reappear, but that was all right with me.

I had never in my life been more thankful for prayer warriors.

One of the ways Mom helped me pass the time and get both our minds off the latest procedure was to maintain my Facebook page for me. There were a lot of posts offering support, and these gave me a tangible feeling of prayers and loving concern. Facebook also let Mom keep our friends and relatives filled in on the news each day. Any positive distraction was welcome.

It was only later that I learned about people posting idiotic conspiracy theories about the Boston bombing being a giant hoax. I realize there are all kinds of viewpoints in the world, and some people still think the world is flat and that Americans never landed on the moon. But I was taken aback when I saw the level of hostility. It, too, was now included in the “new normal.” I recognized that I could never go back, in the sense of returning to the old normal, but I would feel unsettled until I could work out what this new normal meant for me and for Noah.

Then there was what I must call a godsend. It began with a wonderful man, a member of our Houston church, who was a stranger to our family until the bombing happened. The congregation had been receiving reports on our recoveries, and he and his wife had heard about Noah and me.

His name was Edd Hendee (I think the second d is silent), and he was a local radio host (who retired shortly after the bombing) who did a lot of philanthropic work, partnering with his wife. He had a strong feeling that my recovery would surely go smoother if I could be moved to a hospital closer to home.

Mr. Hendee happened to be in Boston for a ceremony honoring his son, who had passed away years before in a tragic skiing accident. So while he was in town, he called the hospital and arranged to visit with me and my mom. He turned out to be a warm and caring man who was as loving to us as anyone could ask. He put us at ease, insisting that I use his first name. After a bit of general conversation, he told us that he and his wife wanted to personally arrange to get me from Boston back to Houston and into an appropriate hospital there, so I could finish recovering near home, as soon as I was physically able to make the long trip.

I tell you, hearing that offer truly had the effect of parting the clouds, especially coming from this kind stranger who knew of us only because he was a member of our local church. We were so moved by his generosity. There was nothing to do but accept and rejoice at this sudden blessing.

I was eager to go, though I wished I felt more recovered inside. But since I wasn’t all that clear on what “recovered” might actually mean, we began getting ready for the move.

Departure day quickly arrived, and it was time for me to be wheeled down to an ambulance to make the ride to the airport. In a moving gesture, the doctors, nurses, and staff lined the hallways and ch

eered when they rolled me out on my gurney. Naomi came in to say good-bye even though it was her day off.

A small medivac jet was waiting to fly us to Houston. This should have been an exciting moment and a new beginning, but my deep gratitude for this philanthropy didn’t protect me from a list of fears and concerns that was growing longer by the minute. I couldn’t explain why. I felt a deep restlessness that seemed to radiate from my bones.

Noah and my dad had gone back on a regular commercial flight, but Mom was able to make the trip with me. Even with Mom’s support, my anxiety level surprised me by spiking as soon as we left the familiarity of the Boston hospital.

I clenched my teeth and set my jaw against sheer panic while they lifted my gurney from the ambulance, placed it aboard the plane, and strapped it down. The gurney took up most of the room, leaving just enough for Mom, a nurse, and a flight crew of a pilot and copilot. The trip took about two hours. All I could do was be mindful of what we were doing and patiently endure the discomfort of all that movement. In spite of the pain meds I was given for the flight, the trip filled me with dread.

I arrived at Memorial Hermann Hospital in downtown Houston to be greeted by a staff who were clearly determined to treat me with attentive care. While I had no doubts about their professionalism, back in Boston I had formed real bonds with a number of the doctors, nurses, and other staff. We were all comrades in the quest to recover. I didn’t realize how much that sense of solidarity had sustained me until it was gone.

At this new hospital, a side effect entered the picture. It didn’t take long to present itself and involved all the medicines I’d been taking.

My new doctors were serious about clearing my system of most of the pain drugs before they would consider discharging me to go home. Since I was totally ignorant of the effects of pain med dependency, I confused my subjective condition with an actual need for the drugs. It suddenly felt impossible to bear the physical discomfort and the emotional instability on top of everything else.

Taking My Life Back

Taking My Life Back