- Home

- Rebekah Gregory

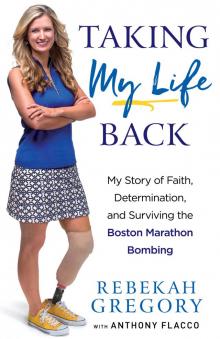

Taking My Life Back Page 11

Taking My Life Back Read online

Page 11

They didn’t need to remind me that there was already little enough anyone could do. By that point I had lived through many months of bedridden time, when I was free to think things over. I had read the investigative findings about the bombers and their methods, the interviews with other survivors, the testimonies of loved ones. I had a much clearer picture than I wanted to have of the misery inflicted by those two killers. I also had a strong sense that it was somehow my duty to understand as much as I could about this thing. And since I knew what I knew, the FBI agents didn’t have to work that hard to convince me.

It was unthinkable that this man’s lawyers might find a loophole to slip him through. There was no way to know if my testimony would prove key to securing a conviction, but if my presence could help in any way, I had to be there.

The clever agents quite accurately judged me to be someone who could never live with seeing the surviving bomber either walk free or take a low-level slap on the wrist as his sentence. The thought that I could be even partially responsible for something like that would be devastating.

Sometimes you can only shake your head. I agreed to testify and to do the best I could. Nobody said I had to like it.

When people ask me how I could psyche up the courage to begin preparing to go to court, I give the credit to the late Fred Rogers of the old TV show Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. His program ran for so many years because of his gentle tone of wisdom. I never forgot his words when he quoted his mother’s advice about coping with disaster and the disillusionment that can follow it. He said she told him to “look for the helpers.” There will always be helpers.

I surely lived through the truth of that. It was only the brave hearts and strong humanity of those first responders that got me and my little boy off of that street alive. They represented the best of humanity, and I can never forget them.

Online, I was grateful for a powerful outpouring of support from all around the world. Here is a small sample of these wonderful messages, and I can attest that these little electronic bubbles of loving energy, thoughts, and wishes did a world of good. They served as personal floatation devices for my morale and no doubt did the same for every attack victim who got such kind support.

Wish there were more people in the world like you. You are truly inspiring and proof that people can be strong and overcome anything. . . . And one more thing, don’t let anyone get to you that is negative about your leg. . . . Just remember you have the coolest leg on the planet!

You truly are a warrior and an inspiration to everyone.

I just wanted to write and let you know that I think you are such an amazing strong person. I have been following your page and it’s very inspiring.

I wanted to say thank you for your inspiring attitude, drive, and determination. Also the humor! (It’s not you, it’s me.)

I’ve found myself in a rough patch lately but your words of hope and encouragement (and I read a lot of them!) have lifted my spirits and given me this excitement for tomorrow! You are an inspiration and God knows every time you post something, or let everyone know you’re having a “human” day too, or share the brilliant things in life you see, you’re opening someone’s eyes to the way life should be seen.

When I read what you post, I have hope. I know I am a survivor and not a victim anymore. . . . God bless you and know you are in my prayers. Nothing will hold you back!

I admire you not because your life is perfect but because your life is a mess and you still find the beauty in every day.

Thank you for being the biggest hero to someone you don’t even know.

I haven’t worn shorts in thirty years and today I saw your post, with you in a dress exposing your fake leg and scars. I decided I could do it too.

If I had tendered any doubts about going through with my trial testimony, these people and so many kind others made those doubts vanish. I could hardly honor those helpers who had swarmed out onto that Boston street in the wake of the explosions unless I took my own opportunity to be a helper as well.

Anytime I felt my determination falter, all I had to do was picture the pattern of blast injuries across my legs and back, remembering that this same pattern would have been across my little boy’s back and head, with his head at the exact level where the worst blast damage was done to my legs. That was all it took to restore my determination.

Without an overwhelming guilty verdict and strong sentencing, there could never be a guarantee that someone else’s child wouldn’t be hit with terrible explosions one day as a direct result of this man’s miserable handiwork. Nobody had to convince me that he had forfeited his right to ever walk free among us again.

For this reason, I had no choice but to live out the example I wanted to set for my little boy and to be consistent with the expectations I placed upon him. In spite of all the wonderful help and support that had blessed me since the bombs went off, this was something I had to take care of myself. It was time to jump on Mr. Rogers’s bandwagon and not just look for the helpers but join them.

There was little formal pretrial preparation for me beyond a couple of interviews, since I was only going to speak about my small slice of that afternoon. Nobody had to freshen my memory of it.

In fact, the persistence of those memories was a big part of my PTSD battle and my constant struggle to beat back the resulting anxiety. I could understand how a soldier returning from combat can find himself or herself flat on the floor because a car just backfired outside. If a trash truck drops a dumpster on the street, a frozen rush goes straight up my spine. And you can probably imagine why I won’t be attending any fireworks displays, yes? The gut-thud of the largest fireworks would only duplicate my memory of the shock wave. Some people who were close to the finish line but not present at the detonations thought that the explosions actually were fireworks. The hairs on the back of my neck probably don’t know the difference between the sounds.

So for the coming trial, my main task was just to embrace the fact that I was going to face this man down in a court of law. If I could focus on the potential positives, this terrible encounter with a true-life monster might actually be an opportunity. The testimony was a fact, but how it would affect me was a matter of my own choosing.

This was another one of those situations that becomes whatever you say it is, as long as you say it with enough conviction and don’t waver under pressure. This is how I was able to shape that piece of reality like a handful of clay and move from fear to determination.

−15−

Serious Improvements to the New Normal

After that milestone, my day-to-day life began to move in a positive direction in things unrelated to athletics. The first inklings of an answer began to form as to how I was going to best use this new lease on life.

I had no idea there were people whose job is to find potential public speakers and represent them. But people at the Premiere Speakers Bureau had seen me in the media and wanted to give me an opportunity to try public speaking. They called with an offer to represent me, provided I was willing to pursue public speaking in a serious way. They explained that they understood the importance of my faith and assured me they would try to book me in places where people wanted to hear a story like mine. Was I interested?

Now, there was no rainbow that suddenly threw an arch over me. Nobody played an ascending glissando on the harp, and there was no one singing “Yahhh!” in musical exclamation. It only felt that way.

There was just me, mouth moving like a silent fish while I tried to find my voice and throw out a hearty acceptance of the idea. I was a nervous speaker who battled stage fright, but the speakers bureau was offering me a chance to use that terrible event as an opportunity to address so many people I would otherwise never reach. This felt like a second chance at life, to do things better than the first time around.

Many of the people I have come to meet through these speaking engagements are my brothers and sisters in Christ. Others are people who don’t share the Christian fait

h but who are sincere in their drive to live their lives on positive terms. I welcome friendly exchanges with all of them, because we strengthen one another’s resolve to remain true to our callings and I believe God uses our longings to draw us to himself.

I don’t have to know the million tiny connections that will fit together to make that happen in each person’s life. Instead I observe that the perseverance, sincerity, spiritual longing, and rise of compassion and empathy will all combine to ultimately lead to a surprise encounter with God, who is as close to us as the sensation of drawing a breath.

When that first phone call with the speakers bureau ended, my insecurities kicked in. I wondered if my ambition to speak would fall flat. Did I want to deal with more media attention? Could I take my thoughts and feelings and form them into the right words, well enough to ask strangers to embrace them? I felt the appeal of the idea but I also felt startled and overwhelmed. All I could do was start writing down words from my heart, which wasn’t hard because writing was how I chose to express myself even as a little girl.

The very next day the speakers bureau called with my first booking. Within a week, they had me booked for the rest of the year.

Okay, wow. Nothing normal about that. Turns out there is a large audience out there who will not ask me to leave out my faith in telling my story. Some are secular audiences, while others can appreciate my spiritual journey for what it is. I wonder if this audience exists because, in the midst of pain and tragedy, we are all hungry for contact with others who live in Christ. We know the recharging that goes along with genuine fellowship, the feeling of the presence of God’s power that comes most strongly in community.

I got a powerful sensation from this opportunity, that of being picked up and swept along. Suddenly, everything was moving fast, just as it had with the fairy-tale wedding. Only this time I resolved to keep my hands firmly on the controls. These first few small speaking engagements were supposed to be my cautious attempt to test the waters with my story. Now it was more than that. It felt like someone lit a rocket engine under me.

I was determined to be deliberate in how I proceeded. My story was more universal than I realized. That meant it was worth slowing things down and doing it right. The number of speaking requests I received revealed a hunger to look at life through a spiritual lens, one that allows us to see the seemingly endless line of disasters and tragedies in the news as being first and foremost challenges to our spirits and to our hearts. We face these challenges best with the simple tools of prayer, dedicated action, and fellowship. They may not change the landscape, but they help us adapt to the terrain.

I spoke in the town of Steubenville, Ohio, and afterward people came by to say hello. A number of them were moved to tears and talked of personally relating to my story of fighting to take my life back, partly from the Boston Marathon killers but also from the internal voices of judgment and limitation that plagued parts of my life.

After this particular event, a boy of about ten walked up with his father. He smiled at me and said, “I have to tell you that you’re my hero.”

My reply was brilliant. I gulped and said, “Really?”

“Oh, yeah. I only came today with my dad, you know, because he wanted to come. But you changed how I see things.” He proceeded to hand me a handwritten note that he had prepared in case we didn’t get to speak, which told me again how much the event meant to him.

This wonderful experience of positive feedback has been repeated in many other places. It never gets old, and it’s one of the best feelings I’ve ever known.

And I have still never found anything more healing than helping someone else. I’m not sure how it works, but just doing it seems to feed my life with invisible vitamins. Things just get better.

The amputation of my left leg was performed on November 10, 2014. Of course, we also had that other explosion two days later with the envelope at the hospital room party, then it was off to rehab and back home.

I was hungry to pump some physical strength into my muscles and bones after so many months of immobility. So two weeks after the amputation, as soon as I was discharged from the rehabilitation center, I went back to my old gym and began to work out again, trying to recapture a little of that old feeling of being strong, of feeling capable. I craved it.

But remember I was only at the Boston Marathon as an observer. Everybody crossing the finish line that day was in better condition than I was. A few years earlier I had tried to run a minimarathon, and even on two good legs it was an ordeal. I had decided that I would never fall in love with the sport and concluded I would most likely never be a runner unless someone was chasing me. I told myself that I burned enough calories on nervous energy to replace a daily run of three miles.

Now I started going in for workouts six days a week, and the gym kindly referred me to a personal trainer. He was a young man who was also a single leg amputee, below the knee. He had lost his leg in a motorcycle accident a few years earlier, and since then he had physically rehabilitated himself and mastered the use of his prosthetic leg. I’m sure you’ve already guessed that I signed up to work with him on the spot.

He proved to be a strong and consistent taskmaster who embraced my goal of regaining my strength. Here’s a sample of his mindset, and the mindset he encouraged in me. The day after receiving my prosthetic leg, I returned to the gym and began wearing it to workouts. But the stump end of my leg was getting rubbed raw, so I heeded my doctors’ warnings not to overuse the prosthesis and the next day decided to go to the gym with my crutches instead of using the prosthesis.

My trainer took one look at me and asked what was wrong. So I told him I was tired of the soreness of using the leg and I wanted a break for the day.

Oops.

He gently but firmly insisted that I must never come to the gym with crutches. I had to promise to get rid of them. “We aren’t just working out the rest of your body except for the missing leg. We’re working out the entire body’s ability to use that leg in the most organic and natural manner that we can. You can’t achieve that by worrying about skin irritation, because you can’t achieve that without the leg.”

Harsh, yes? Maybe harsh is just what I needed, because as much as I wanted to remain positive in my recovery, the lifelong task of living with this thing felt like looking up at Mt. Everest from the base.

The truth in his words was plain, and I couldn’t see any way forward except to embrace it. From then on, I did the workouts with the fake leg and without the crutches. Part of my new normal was this: from now on, unless I was wearing that leg, I would never be fully dressed.

My main workout was structured around heavy core work. General aerobic exercises of all sorts were added to fire up the process of regaining vital strength for my heart and lungs. Since my blood pressure was always lower than normal because of the remaining effects of POTS from my teen years, I focused on raising it with the physical effort of the workouts.

At home, I struggled with the aftermath of pulling apart this little family. That situation guaranteed that I had plenty of stress energy to work out at the gym.

When New Year’s Eve rolled around and I took my first steps in the new artificial leg alone, I firmly acknowledged not only that the marriage was no longer a part of my life but also that my fake leg was now a permanent part of it. I accepted these two truths, but they gave me the distinct sensation of falling into a hole and dropping at high speed.

As for the new leg, I took my first walking steps between a pair of handrails, for stability.

The physical feeling of standing up was good, but I could instantly tell that this was going to be radically different from the way I remembered standing. Here you are, I told myself, working on my confidence on New Year’s Day. You are more or less upright, without using crutches, for the first time since April 15, 2013. The view from here, standing up fully straight and without hunching over crutches, back straight and eyes forward, is a familiar view from the old normal. You remember th

is.

I had two legs beneath me now, but I could only feel the ground with one of them. The sensation reminded me of times when I still had two good legs but had slept in a funny position so that one leg fell asleep. We all know that sensation of standing up on a leg so numb that you can’t feel it. Now I had the same sensation, only this time the missing leg was no illusion. When I stood up on the prosthesis, the leg clearly didn’t belong to me. It really made it hard to find my balance.

It was immediately apparent that I would need intense practice to develop the necessary skill. And good balance and smooth movement would require strong support from every one of the muscles I was working to build up at the gym.

When I considered the challenge, it felt like something I could learn to do but only after serious practice. It would take a lot of hard work before I would be able to move with sure steps on this new leg and carry myself with any sort of grace.

I embraced the task. But while I went through that first process of walking between the parallel bars, ready to grab them if I needed to, this new challenge of learning to operate a foreign object as if it was a part of my body felt like the idea of learning how to ride a unicycle.

By that I mean most people could learn to ride a unicycle if they had a strong enough reason to endure the process of finding their balance on it. Why, they could bring their unicycle into my physical therapy lab and share time on these same parallel bars, just as I was doing on the leg.

And the strong and positive side of human nature pretty much guarantees that somewhere out there is a determined someone who also stands on an artificial limb (or two) and has now mastered walking and running—and will next learn to ride that unicycle, and maybe juggle while doing it.

I understand that level of striving. It’s buried in the nature that drives us, is it not? Even as we lament the terrible dark sides of humanity that can sweep over us from time to time, it’s glorious to consider the great accomplishments that our same human nature can achieve.

Taking My Life Back

Taking My Life Back